Understanding Market Returns

A simple guide to the three forces that power your investment results

Many people compare capital markets to roulette, but this comparison misses an important point. With roulette, you’re likely to lose money over time because the odds are stacked against you. In contrast, capital markets generally offer a positive expected return.

Where does this positive expected return come from? To understand this, let’s break down its three primary sources.

Risk-Free Return

When you buy government bonds in your own currency and hold them until they mature, you’re basically guaranteed to get back the amount promised. That’s because the government can always create more money to pay its debts. (Of course, whether that money will be worth as much in the future is another story, which we’ll cover in a future post.)

The return achieved this way is the most fundamental form of positive return. Currently (mid-October 2025), the US 10-year yield is around 4 per cent, meaning if someone invests for 10 years and doesn’t want to take nominal risk, they can expect a return at this level.

Risk Premium

Imagine you have a business idea but need funding. To get started, you can raise money in two main ways, but both require investors to accept risk to earn a return.

One way is to borrow by issuing bonds, promising to pay interest and return the principal at maturity. If your business struggles and can’t repay, creditors are first in line to claim any remaining assets. Because there’s a risk of default, investors demand a higher return—the risk premium—compared to safer government bonds.

You can also sell shares and bring in equity partners. Shareholders share in profits, potentially through dividends or rising share values if profits are reinvested. However, shareholders get paid only after bondholders, so they face higher risk and expect an extra return—the equity risk premium.

The Mystical Alpha

If you don’t feel confident picking individual investments, you can buy an index fund tracking the whole market. You’ll be a passive investor and earn market returns (risk-free return and risk premium, where the latter depends on your chosen market and portfolió composition).

Alternatively, if you think you can outperform the market, you become an active investor aiming for ‘alpha’ – any extra return above the market average.

A Simple Numerical Example

Let’s look at a simple example. Over the past year, US one-year government bonds paid 3.5%. The global stock market returned 6.0%. But if you’d carefully picked your own stocks, you might have made 7.4%. Here’s how those returns break down:

Risk-free return: 3.5%

Risk premium: 2.5% (6.0% - 3.5%)

Alpha: 1.4% (7.4% - 6.0%)

Now, let’s examine what historical data reveal about these sources of return and what might be expected in the future.

Risk-Free Return

Government bond yields have fluctuated widely over the past 50-80 years, and there are currently significant differences between countries. Investors should use government bonds in their own currency as a baseline. That is, if you want to invest in euros for 10 years, you can calculate with a return of around 3 per cent, which is currently the approximate yield of a 10-year euro government bond. Conversely, if you invest for 5 years in Swiss francs, you can expect a risk-free return of 0 per cent, which is the yield of the 5-year maturity Swiss government bond.

Risk Premium

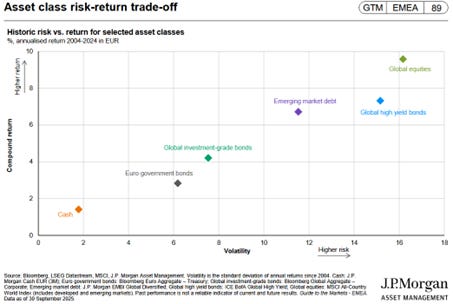

The risk premium—the extra return investors demand for taking on uncertainty—varies across assets and countries. History shows that the more an investment’s value fluctuates, the higher the return investors generally expect as compensation for that risk. This helps explain why stocks typically outperform corporate bonds over time: shareholders take on greater risk, receiving payment only after bondholders, whether from company profits or in bankruptcy. In return, they expect—and have historically earned—higher long-term returns for shouldering that uncertainty.

You’ll also notice that lending money for longer periods (like buying long-term bonds) usually earns you a bit more interest than lending for short periods. This extra reward, called the maturity premium, is typically about 1%.

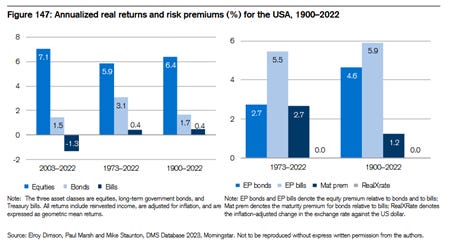

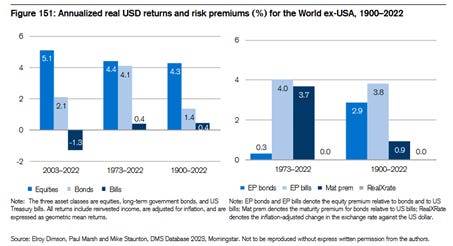

Stocks tend to provide higher returns than bonds, with an extra return for taking on stock market risk of about 2-3% per year. Most data comes from the US, which has some unique factors:

The US moved from a developing country to a superpower over the last 130 years.

There were no wars on US territory during this time.

US valuations rose sharply from the early 1920s, reflecting a willingness to pay more for earnings and assets.

These factors likely make past US returns higher than what to expect in the future. It’s wise to use a lower long-term risk premium when planning.

The following two charts show the long-term returns of the three most essential security types (equities, bonds, money market instruments). In this case, the only difference between bonds and money market instruments is maturity. The former involves long-term lending, while the latter involves short-term lending.

Alpha

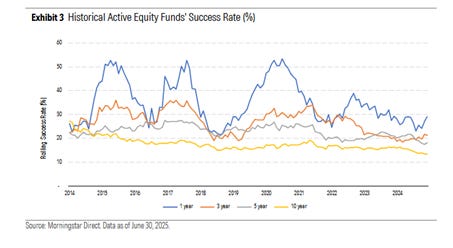

There’s fierce competition in the markets—many experts are all trying to achieve the best returns. Unlike the other two sources of return, beating the market is a zero-sum game: if one investor does better than average, someone else must do worse by the same amount.

Since the market consists of both active and passive investors, their overall returns, before costs, average out to the market return. Because passive investors match the market and active ones face higher costs, the after-cost return for active investors is typically lower.

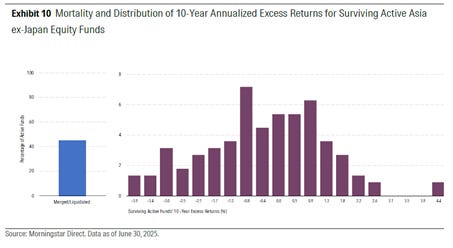

Morningstar regularly publishes the so-called success rate. This shows what percentage of active investors achieve better performance than passive investments.

Still, some investors do manage to beat the market by 1–2 percentage points per year after costs, depending on the market and the period.

Lessons for Portfolio Construction

The first two types of return (risk-free return and risk premium) don’t require any special expertise. Anyone who buys government bonds or stocks can generally expect to earn these returns, thanks to the work of millions of other investors and analysts who keep markets efficient.

‘Alpha’ is not guaranteed. Achieving it requires a real edge over other investors. Most people lack this, and studies show few consistently beat the market.

It’s usually best to build your portfolio around the risk-free return and risk premium. These are unconditional, so no competitive edge is needed. Alpha requires an advantage, and data show it’s like roulette, with negative expected compensation. It should only have a small part in your plan, if any.

Understanding the three sources of return can help guide your investment decisions. By focusing on the predictable components and being realistic about the challenge of earning alpha, you can build a stronger investment strategy.

In a future post, we will discuss what else is worth considering when constructing a portfolio.